A fact often ignored in policy discussions is how critical areas of decision-making – on economic growth, climate change, energy availability and solutions – interact and how this interaction makes certain policy results impossible even though they are vigorously pursued in present-day politics. Here we pose some key questions, which highlight these profound linkages.

We first analyse our options for keeping temperature rise at or below 2°C – the official target discussed in our section on climate change – from the perspective of the availability of energy resources in the face of continuous global economic growth. We pose three questions:

Question 1: Connection Between Economic Growth, Energy Use and Climate Change

1. Can global economic growth continue as before – with growth rates higher in BRICS-countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) and somewhat or clearly lower in North America, Europe and developed Asia – while we are simultaneously and successfully limiting global temperature increase to 2°C by 2100?

The answer is clearly no. As we discussed in previous section the non-availability of cheap energy sources for world economy may well itself slow economic growth quite separately from efforts to limit global warming. But here we are interested in the interconnections between global economic growth and achieving climate change targets.

It is clear in looking at global energy resources that we are not running out of either oil, coal, or gas as we have plentiful supplies of such energy resources. But the critical issue is how to convert these resources into energy flows to the global markets that growing economies need in an environmentally and economically efficient, cheap and thus politically acceptable manner in face of accelerating demand especially from BRICS-countries. And here comes the question that has to be answered by all economic policy-makers if we are serious about the well-being of future generations:

How do you achieve climate change goal of 2°C by 2100 with present use of fossil fuels in a world economy that grows steadily although unevenly?

The biggest challenge for policy-makers in this connection is that, as mentioned before, according to the most recent estimates only 20 percent of current proven fossil-fuel reserves can be burnt to have a reasonable chance of remaining at or below the 2°C target.52 This means in practice that we, as a global community, have to reduce drastically our reliance on fossil fuels at the same time as:

• BRICS-countries and some other emerging economies will have clearly increased energy demands; and

• Environmentally acceptable energy resources – and in particularly the cheap ones – are clearly diminishing as discussed in the previous section.

Acceptance of these facts would result in fundamental change in present global economic and energy policies. We are still far from realizing the fact that most oil, coal and gas reserves are unburnable which brings us to the brink of another big calamity, a major new financial crisis. The Guardian reported on 18 April 2013 on this “carbon bubble”:

“The world could be heading for a major economic crisis as stock markets inflate an investment bubble in fossil fuels to the tune of trillions of dollars, according to leading economists. “The financial crisis has shown what happens when risks accumulate unnoticed,” said Lord Stern, a professor at the London School of Economics. He said the risk was “very big indeed” and that almost all investors and regulators were failing to address it. The so-called “carbon bubble” is the result of an over-valuation of oil, coal and gas reserves held by fossil fuel companies. … these reserves will be in effect unburnable and so worthless – leading to massive market losses. But the stock markets are betting on countries’ inaction on climate change. The stark report is by Stern and think tank Carbon Tracker. Their warning is supported by organizations including HSBC, Citi, Standard and Poor’s and the International Energy Agency. The Bank of England has also recognized that a collapse in the value of oil, gas and coal assets as nations tackle global warming is a potential systemic risk to the economy, with London being particularly at risk owing to its huge listings of coal.” 53

Our Remaining Two Questions Are:

Question 2: Connection Between New Technology, Economic Growth and Climate Change

2. Can technology help us move quickly to make the use of fossil fuels less polluting so that our global economic growth model can continue and we will stay below the 2°C target by 2100?

The answer is also a clear no. New technology will undoubtedly be a major contributor to solving the climate and energy dilemma, and may allow the continued use of some fossil fuels. However it is unlikely to be available in the time, or to the extent, required to allow for widespread fossil fuel use if we are serious about taking action on climate change.

Question 3: Connection Between Alternative Energy Sources, Economic Growth and Climate Change

3. Can our global economic growth model continue if we quickly move to the alternative energy sources – such as renewables and nuclear – in an emergency programme to remain below the 2° C target by 2100?

Here also the answer is a clear no. The present alternatives—primarily solar, wind, and nuclear—contribute only a small proportion of global energy supplies relative to fossil fuels (see graph 26). Thus their replacement of fossil fuels while maintaining global economic growth is highly unlikely in the short term (5-20 years). But they may provide a longer term solution for mankind and a steady-state economy. These technologies are improving extremely rapidly and their costs are decreasing.

The conclusion is that unless we, as a community of nations, have the courage to address climate change seriously, we will enter a period of escalating economic and social crises. e only solution is for global economies to be rebooted towards genuinely sustainable modes of operation. is represents a true dilemma for governmental decision-makers as will be discussed in the next section.

Options for Mankind

To address the interconnections between climate change, energy availability and economic growth is not an easy task for world decision-makers. The next chapter of the Manifesto will briefly discuss the fact that time is running out, and that the longer we leave it, the fewer options we have to turn the tide. The key here is to move quickly from the use of fossil fuels as a basis of our economic growth, poverty reduction and prosperity. Other measures are also important – such as to improve the sustainability of our buildings, forestation and stopping deforestation just to take a couple of examples – but nothing else compares to the role of fossil fuels in accelerating climate change through its massive contribution to the increase in carbon dioxide emissions in recent decades.

But here lies the big problem for mankind. Moving from fossil fuels to alternative sources of energy – renewables and nuclear – takes time and the process is bound to affect in fundamental ways economic growth rates in the countries of North, South, West and East. Would the politicians and political leaders have courage to address this problem, honestly?

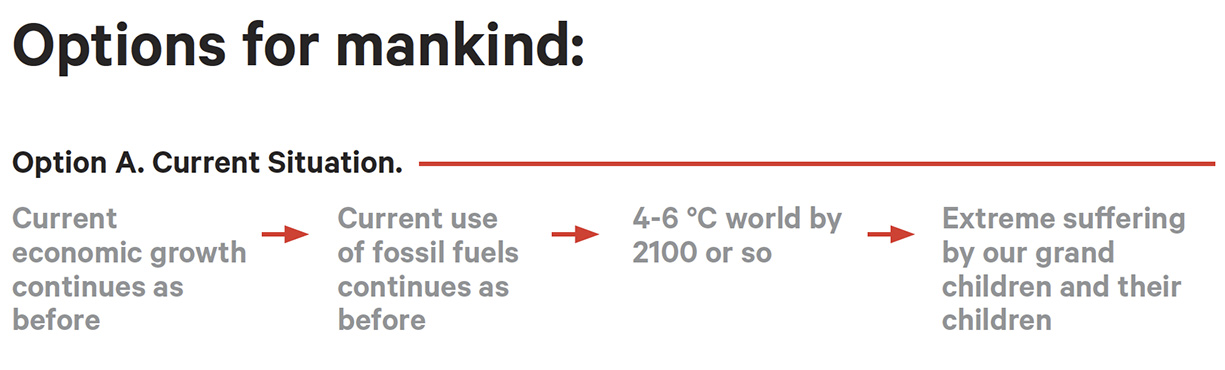

OPTION A. Current Situation:

The following two charts illustrate the problems we are facing right now. Option A describes the current policies of the countries on the globe with “business as usual” economic and energy policies – as starting point for future world economy. This will bring about a world of 4-6 C° which no one wants but at the moment the political decision-making system throughout the world is set up to continue as before.

But if world leaders finally realize that we cannot go like this anymore – as it is morally and ethically wrong to burden future generations with an unsolvable climate change crisis – we have to make a big change in our economic and energy policies to stay below 2°C by 2100. Then the prospects for decision-making do not look easy as illustrated in Option B. As will be discussed in the next section the intergovernmental climate change negotiations are set up to try to reach a major deal in 2015 on a binding climate change agreement which should ideally keep temperature increase below 2°C, even though 2°C is too high. is is the basis in the chart in describing the political realities governments have to face in reaching this deal.

OPTION B. 2°C World:

Option B describes what would be needed to achieve this goal from the point of key variables and argumentation discussed in this section, namely that the use of fossil fuels should be phased out in 2-3 decades, and a massive transition to a new economy centred around renewables, nuclear, energy efficiency and conservation should start immediately. But, realistically, this would bring about a lot of disruptions to the world economy so there would be huge pressure not to reach a binding deal in 2015 but rather a face-saving postponement – with marginal agreements on some secondary or preliminary measures – as has happened before many times over. This sad result would not mean much in terms of changing the future of the mankind.

Another aspect of the politics of climate change is that both science and the role of fossil fuels in climate change, as described here, will be down- played by those private and public vested interests who benefit from the present situation. So the box “Movement to get out from a binding deal” will be fueled by special interests that have a lot of financial resources to spend for a campaign to water down the deal. And so far they have always been successful together with overall ignorance of governments of the seriousness of the global dilemma as described above. Could this be changed?